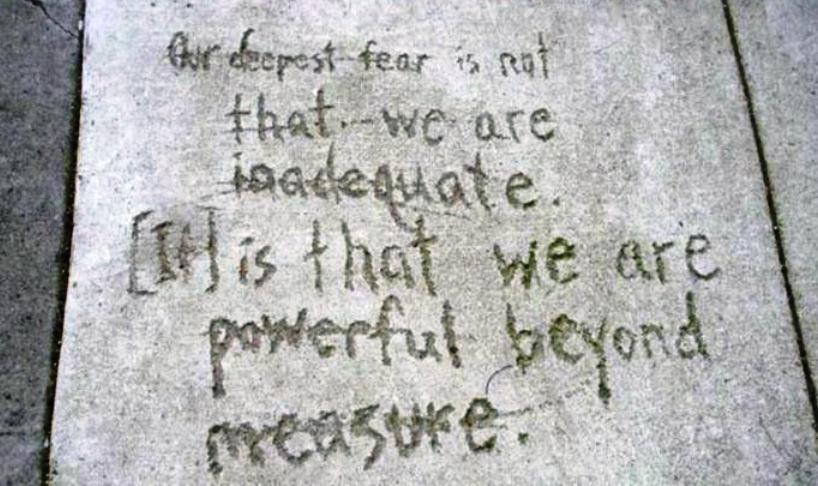

Feel the fear, but do it anyway. This is about how I felt “the fear” but said screw it, and spent 5 days in the Arctic wilderness of Norway, driving a pack of huskies across the tundra.

It’s an often-repeated mantra in business and in life, but it has become so often repeated that it loses its power. It’s easy to say for million-selling authors and business gurus, but it can be harder to put into practice when you’re still 20- or 30-something and struggling to find your own place in the world.

In 2009, I hiked the Inca Trail; it’s another story for another time, but it started something. It was meant to be my one big thing: I wanted to be one of those people who did things. And Peru was mine. Except it didn’t stop there: I knew I had to do more.

After I overcame my fear and signed up for an Arctic adventure, I had about 9 months to prepare. But despite preparations, nothing like this seems real until the morning when your alarm wakes you up in a cold and lonely hotel room, while it’s still dark outside, you wonder aloud whose stupid idea this was, but get out of bed and the adventure begins.

That’s where it can all change.

You can be someone who presses snooze, or someone who watches life on television. Or you can curse yourself for stupid ideas, but do them anyway.

For me, after months of planning, months of training, and countless freakouts when I thought about what I was doing, the adventure was no longer “next year”, or “next week” but instead…now.

Reading back over the adventure’s itinerary, I’m wryly amused that the first day of dog sledding is described as follows “we are briefed on how a dog sleds works and how to use the ice brake and snow anchor. We then put the theory into practice and some time is spent getting used to the basics of sledding”. This makes it sound a lot more…instructional than it was. First of all, how does a dog sled work? Four dogs pull the sled, you stand on the back and don’t fall off. We’re not talking about driving a car, here.

The brake that was mentioned? To return to the car analogy, imagine if you had brakes that stood little to no chance of actually stopping the car. The brake was a metal bar between the two runners – you stand on the bar, it digs hooks into the snow and ice, and this slows and stops the sled. But when the dogs wanted to run even standing on it with all my weight and both feet wouldn’t hold them back. Four eager and hyperactive huskies against a marketing nerd…

But sometimes instruction is overrated, and the first day was incredible. The dogs went off like a rocket; through the woods and down the trail — there was no need to shout instructions or directions or “faster”, the dogs knew the way and you just had to try and slow them down. Down slopes, over humps — the sled would take off briefly, before landing back to earth with a thump — the dogs just want to go, just want to run, on and on and on.

My fear was nowhere to be found any more.

The grouch who didn’t want to get up the day before may as well have still been in London, because I was flying across tundra, shouting encouragement to my pack of huskies. This is surely what they mean when they say feel the fear and do it anyway.

The first day I was lucky enough not to fall off the sled. The second day felt like I spent more time falling off the sled than standing on it.

I learned my lesson quickly, though, because by the third time I fell — because these things always seem to come in threes — I held tight. Guess what? The dogs still didn’t stop. The sled stayed upright, however — which was a blessing, because although I was being dragged behind a speeding sled I managed to slow it down enough to climb back on.

From my notebook at the end of the third day “Today was a great day — such a change from yesterday. I decided first thing that I’d stay at a pace I felt comfortable with — and at first I was fearful and nervous of falling off. Then someone behind me told me not to hold my dogs back, to let them run.

Something changed.

The best I can describe it is it felt like snowboarding — you relax, bend your knees and just slide with it. From there I was on top — I didn’t brake unless it was a downhill and I might run over a dog.

I passed half of the group on a straight, and the sun shone on the frozen lake. The patterns made in the snow looked like the curtains of the Northern Lights.”

Sometimes it seems I have to learn the same lesson over and over again.

It’s OK to be scared, but you have to feel it and then just ride it out. Sledding across lakes was a great feeling — the dogs could run their hearts out, and I’d shout words of encouragement to them. I no longer felt that I had to stay at the back of the group, and let my dogs overtake over sleds if they could. I felt like there was nothing I couldn’t do, and as the sun shone on me I could see a shadow of me and my sled racing along and keeping pace alongside me.

That’s how it goes. Looking back on some days I remember pain and hurt or just the endless whiteness of the tundra, then I remember the thrill of racing across frozen lakes, or down winding forest trails and I smile as I remember my favourite dog, the affectionate Anneka who loved attention.

I was a marketing nerd who’d get out of breath running a bath, but I did it anyway. It was about more than the Arctic or the dogs, or the £6,000 I raised for charity in the process: it was about setting myself apart as someone who did the things he talked about.

There’s a world out there to be seen and experienced, and unless we face the fear we only ever see a fraction of it.

James Chesters is an explorer, adventurer and writer living in London, England. He aims to share his stories to inform, entertain and, hopefully, inspire others to explore the world — while also expanding his own horizons. The rest of the time, James is a copywriter, freelance journalist, and community/marketing geek promoting things that are important to him. Read more from James at jaychesters.tumblr.com and follow him on Twitter @jameschesters

Image Credit: novamentis.wordpress.com